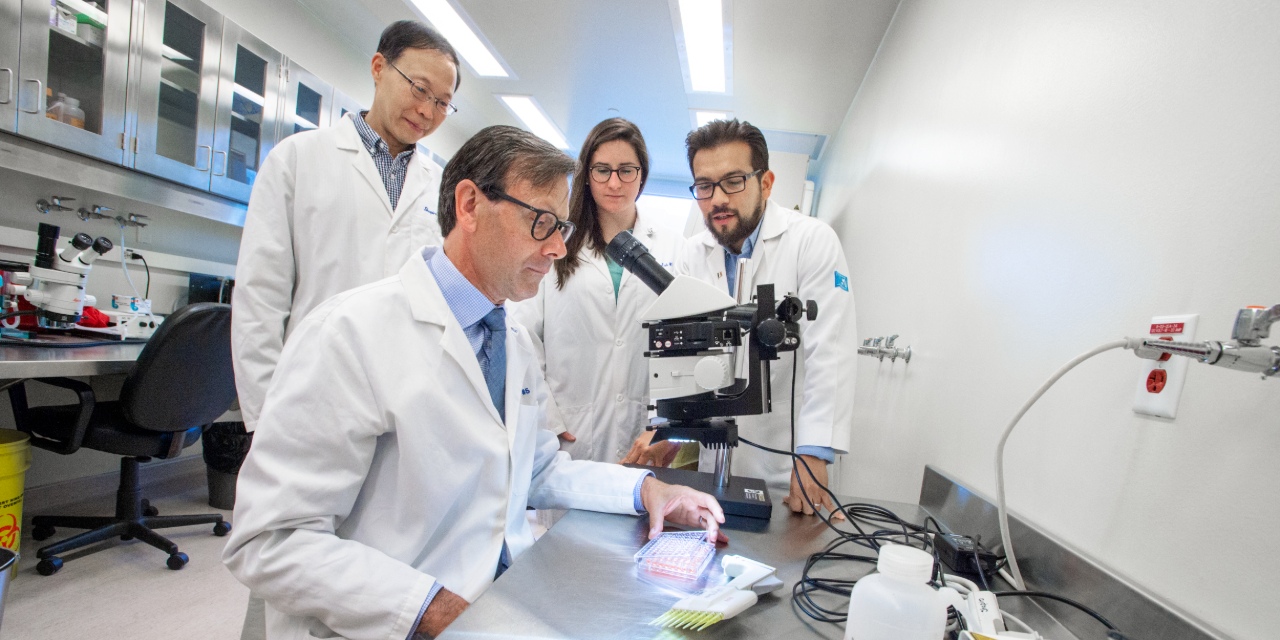

James Shapiro with his team in the U of A's Clinical Islet Transplant Program. Shapiro developed the Edmonton Protocol for treating Type 1 diabetes after performing the world's first human islet cell transplant in 1999. (Photo: Richard Siemens)

Melanie Hibbard's son was four years old when he was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes (T1D). Just over a year later, Hibbard's youngest child-just 18 months old-received the same diagnosis.

"I often tell people it's like being kicked in the stomach. It changed our lives forever," says Hibbard. "I remember the nurses and the doctors looking at me and saying, 'Don't worry; as long as you do everything that we taught you, they will stay alive.'"

Being a parent of children living with T1D has shaped Hibbard and is the motivation for the most recent chapter of her life as executive director of the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation Canada (DRIFCan). The Edmonton non-profit organization is devoted to advancing T1D research at the University of Alberta in hopes of finding a cure.

"Our goal is to give as much funding as possible directly to cure-based research that is happening right here at the U of A," says Hibbard, "and it's incredible to see how quickly the work is moving forward."

DRIFCan was established in 2005 to help advance the Edmonton Protocol-a groundbreaking procedure pioneered at the U of A to help patients with T1D become insulin-independent through islet transplants. The organization led a grassroots campaign to raise funds for the research until DRIFCan temporarily went dormant in 2010.

In 2015, it was reborn with a new board and a renewed sense of purpose. Once it had re-established its footing, the organization began fundraising again in earnest and over the past two years DRIFCan has contributed more than $500,000 for U of A research. The funds go directly to efforts led by James Shapiro, the Canada Research Chair in Transplantation Surgery and Regenerative Medicine and director of the Clinical Islet Transplant program at the U of A.

"We're really proud to be supporting Dr. Shapiro and his team," says Hibbard. "For decades now people who have been diagnosed have been told by their doctors, 'Don't worry, a cure is on the way.' But it's never been more true than it is today. When you meet or speak to Dr. Shapiro, it's evident that it's going to happen."

"Melanie and the DRIFCan team remind us every day that we're not working on some fancy academic exercise here, but are laser-focused on a cell transplant-based cure for diabetes to make a difference for children and adults with diabetes across the globe," says Shapiro. "DRIFCan not only helps us focus on the mission, but their generous funds are absolutely key to accelerating the path forward from the petri dish to the patient."

While Shapiro's work was first focused on islet transplants as a potential cure for T1D, limitations to the approach have since emerged, including a finite supply of islet cells available for use and the need for patients to be on lifelong immunosuppression drugs post-transplant.

Shapiro's team is now testing several promising new avenues, including the use of stem cells, which can become islet cells when transplanted into the body, as well as a new technique to make islet cells from the blood cells of a patient's own body-potentially bypassing the need for immunosuppression drugs altogether.

While it's still unclear where the next big breakthrough will come from, Hibbard is confident DRIFCan and the research happening at the U of A will be part of the solution.

"That's why we're funding this work; because we believe in it," says Hibbard. "Ultimately our goal is to close our doors, because that means there's been a cure."