To ensure food security by 2040, consumers need to embrace non-traditional technologies under development and some not even thought of yet, according to Dr. Bill Aimutis, director, North Carolina Food Innovation Lab, NC State University.

If, as the United Nations predicts, the world's population will nudge toward 10 billion by 2050, today's global food supply will fall short by approximately 40 per cent. And when it comes to protein, farmed animals will not be enough.

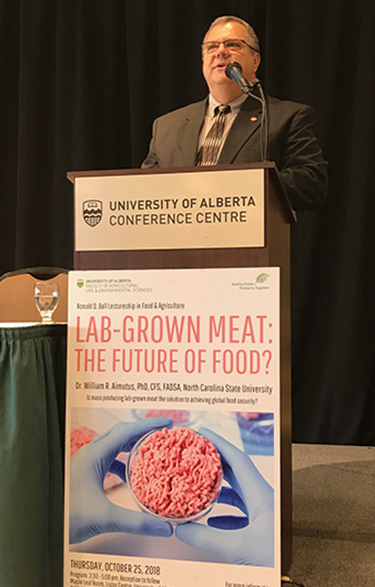

More people with more money have led to an increase in the consumption of animal products, said Dr. Bill Aimutis, director, North Carolina Food Innovation Lab, NC State University. Aimutis was a speaker at the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences' (ALES) second Ronald O. Ball Lectureship in Food & Agriculture on Oct. 25. He spoke to a crowd of nearly 300 about cellular meat, also known as cultured meat or in vitro meat.

The current global protein per capita consumption is 76 g/day. People in developed countries consume 103 g/day. If we continue to eat this amount, by 2050 we'll need to increase current protein production by 32 per cent. If developing countries continue to increase protein consumption toward 103 g/day, as they have been doing for the past decade, we'll need to increase our protein production by nearly 70 per cent.

The solutions to protein shortages include staying within recommended daily amounts, reducing food waste and eating alternate nutrition sources, said Aimutis. One of the solutions is cellular meat, a concept that grabbed the world's attention in 2013, when a Dutch scientist named Mark Post cooked and tasted the first lab-grown burger on live TV.

It was more than a decade earlier, however, that cellular meat was launched. NASA funded a group of college students to develop a muscle protein production system for long-term space travellers. The team grew goldfish cells in a lab and created a structure that resembled a fish filet. Their work was published in 2002.

The recipe for making cellular meat starts with removing cells by biopsy from living animals or animal embryos. The cells are introduced into a nutritional growth medium containing proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and growth-promoting hormones. They are then incubated in a body temperature environment to grow into a mass that is harvested and processed into a meat-like substance. Most cellular meat will be used in minced or ground products and won't look like a Fred Flintstone steak.

Uncertainty versus necessity

At the University of Alberta, Mirko Betti, associate professor in ALES' Department of Agricultural, Food & Nutritional Science, co-authored a 2009 paper about in vitro meat with Isha Datar, a Faculty of Science graduate who is executive director of New Harvest (a non-profit research institute dedicated to the field of cellular agriculture - essentially, making animal products without animals). The study outlines the technology involved, as well as the possibilities and challenges.

"There was some skepticism from our peers when that paper came out," said Betti. "Some people thought it was science fiction."

Although Betti has not received major funding in the field of in vitro meat, an NSERC individual grant allowed him to conduct complementary research on cultured meat by studying how to replicate the meat factor through fibroblast culture.

"We need ingenuity to help feed the world," said Betti. "It's either have a lower population or come up with solutions to food shortages."

"It will be important during the next decade to emphasize how technology can play critical roles in mankind's survival and geo-political stability," said Aimutis. "We need to take risks or we won't have enough food."

Aimutis thinks there could be small quantities of cellular meat ready for consumption within 10 years, but potential regulatory issues could hold up the process.

"We don't even know if it will be classified as meat," he said.

Aimutis emphasizes that the global community must band together to find solutions to the problem of food insecurity.

Betti agrees.

"We are becoming more and more a global economy," he said. "We need to share resources and ideas."

"Many of our agricultural practices must change," said Aimutis. "The consumer might need to be more accepting of some of our livestock practices, and we just might need to consume products like cultured meat, insect proteins and other foods that today present a certain yuck factor to us."

Benefits of cellular meat

Less soil depletion

Reducing water used to grow crops and rear and slaughter animals (water demand will increase by 40 per cent by 2050)

Fewer greenhouse gases emitted from animals

Less energy use

The meat is less prone to biological risk and disease, such as Hoof and Mouth Disease and Mad Cow Disease

No likelihood of fecal contamination

The meat could be healthier because it can be produced with less undesirable fats

Livestock ranchers would be less reliant on climate and land quality and area

Less food waste from processing

Challenges of cellular meat

Cost of labour and facilities

Cell cultures are easily contaminated and killed

Consumer perception

Regulatory delays

Taste: meat gets much of its flavour from bloody and muscle, and researchers don't yet know what components of blood give its flavor

Who will eat cellular meat?

Nearly two-thirds of people polled said they would try cultured meat, and one-third said they would eat it regularly.

Men are more interested in cultured meat than women.

Vegans perceived cultured meat as more natural than farmed meat, and both vegetarians and vegans perceived cultured meat as more appealing than farmed meat. Neither group was willing to replace their meat substitutes with cultured meat.