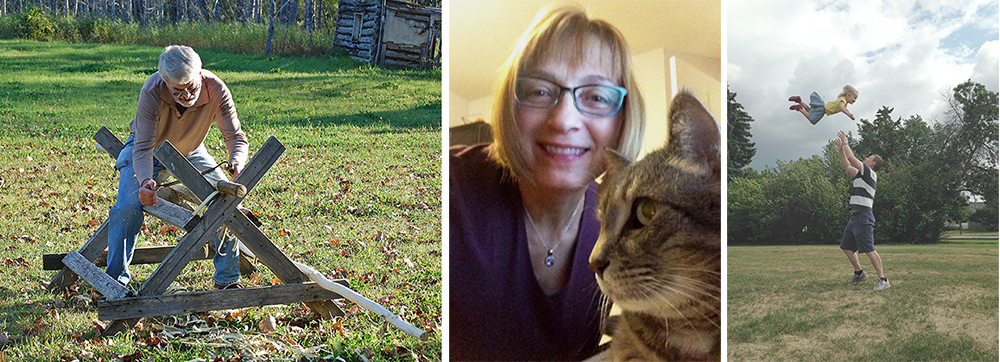

From left to right: Harvey Krahn on his farm, peeling logs; Nancy Galambos with cat Jonas; Matt Johnson playing with daughter.

Happiness matters.

Happy people live longer, they are healthier and are more likely to engage positively in their communities, and they also cost less to the health-care system and to society in general. Happy people may be cheap, but does happiness decline as young people move into early adulthood and midlife, and then increase again, as various proponents of the "U-curve of happiness" have argued?

The answer is no, according to a newly published paper based on data drawn from a 25-year longitudinal study by University of Alberta researchers Nancy Galambos (Psychology), Harvey Krahn (Sociology), Matt Johnson (Human Ecology) and their team. Contrary to widely disseminated (and oft-quoted) studies, happiness does not stall in mid-life. Instead, there is an overall upward trajectory of happiness beginning in our teens and early twenties.

Up, not down: The age curve in happiness from early adulthood to mid-life in two longitudinal studies refutes the claim that happiness is the domain of youth-that it's all downhill once the stresses of adulthood kick in. "I think it's important to question conclusions that have already been drawn about mid-life happiness," says Galambos, commenting on the cross-sectional research (comparing different age groups at a set point in time) that incorrectly informs so much of the academic and popular opinion about happiness.

"Cross-sectional research is easier to do," says Krahn. "But if you want to know with more certainty how individuals change, you can't compare people of different ages." Comparing an 18-year-old to a 43-year-old often fails to take into account differing life experiences, such as ethnicity and generational differences. "I'm not trashing cross-sectional research-we all do it for other research questions-but if you want to see how people change as they get older, you have to measure the same individuals over time," he says. "You've got to look at longitudinal data."

In other words, longitudinal research tells a better story-or at least, a more valid one.

In the Edmonton-based study, which followed one cohort from ages 18 to 43 and another from ages 23 to 37, the story reads more like a novel, generating data (and additional papers) not just on happiness, but also many other aspects of overall well-being. In this particular study, the researchers simply asked participants, How happy are you with your life right now? Response options ranged from not very happy to very happy. The researchers note that they did not define happiness for the participants, nor did they ask for specific examples of happiness.

Although the happiness trajectory over this age period generally pointed up, not everyone in the study followed this trend. "If I'm divorced and unemployed, and I have poor health at age 43, I'm not going to be happier than I was at age 18," Galambos says. "It's important to recognize the diversity of experiences as people move across life."

Governments around the world are listening, and in Canada, gathering information about happiness is part of Statistics Canada's General Social Survey questionnaire. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ranks Canada ninth in general life satisfaction, ahead of Sweden and the United States.

"It seems trite-just be happy-but behind that are the policies shaping society," says Krahn. "The policy implications of the study are about changing the conditions that cause grief, like being unemployed, like losing your home, inequality, being a refugee, crime, addictions-these things will make you less happy, age notwithstanding."

The researchers cite the U of A's recent introduction of a fall reading week as a positive investment in the well-being of its most vulnerable population-students.

"We know that students in university are among the most depressed in society," says Galambos. "And so I talk about this research and similar research with my students. Things can improve, and if you take care of some mental health problems such as depression and anxiety now, you might prevent them worsening in the future."

"Happiness matters," says Krahn. "For people's own well-being and community well-being, let's design a more social world that allows more people to be happy, even if they're grumps at heart!"

Up, Not Down: The Age Curve in Happiness From Early Adulthood to Mid-life in Two Longitudinal Studies was published in Developmental Psychology by Nancy Galambos (Psychology), Shichen Fang (doctoral student/Psychology), Harvey Krahn (Sociology), Matthew Johnson (Human Ecology) and Margie Lachman (Brandeis University)

In celebration of this study, we have declared January HAPPINESS MONTH! We want to know what makes YOU happy. Something makes your day better, and we'd like to know what that is. There are many ways to participate: tweet to our @UofA_Arts account using the hashtag #HAPPYJAN, send a selfie to our Instagram account (@UAlberta_arts), or email us at artsnews@ualberta.ca

Watch for the collected happiness wisdom of our Arts community in the coming days. Thank you for your participation, and happy January!