One hundred years ago this month, the so-called Spanish flu swept across the globe infecting a third of the world's population and claiming somewhere between 50 and 100 million lives, far more than were killed in the First World War.

It took almost a century to reveal the secrets of one of history's most deadly influenza pandemics, according to Stephanie Yanow of the University of Alberta's School of Public Health.

In its immediate aftermath, the unprecedented health crisis gave rise to many of the protocols Canada uses in responding to pandemics to this day, while the virus itself eventually provided an invaluable key to modern strains of the disease.

The First World War provided the perfect conditions for the flu pandemic to spread-exhausted soldiers sick with other infections in trenches, crowded military camps, boats carrying fresh troops to the front and returning with the infected, said Yanow.

At the end of the war, huge numbers of soldiers returned home, many bringing the virus with them. In Canada, the pandemic quickly spread west, devastating communities amidst a severe shortage of doctors. All told, 50,000 died in Canada, 4,000 in Alberta.

At the U of A, the second wave of the pandemic (the first arriving in spring) hit just as students were starting a new term, many having just returned home from the front. By October, the university was "disbanded" to treat the ill and prevent further infection, said U of A historian Sarah Carter.

Pembina Hall, then a women's residence, was transformed into an emergency hospital, and by November, 70 people had died of the flu. Among them were students, staff, volunteers and one of university's first four professors-William Muir Edwards, who succumbed caring for the ill.

No immunity

One of the reasons the pandemic was so deadly, said Yanow, was that the virus was completely new. Humans had no immunity to it.

"This was one of our first experiences of a disease on such a global scale, especially in the context of the war and this massive movement of populations carrying disease to all of these far-flung places," said Yanow in a School of Public Health lecture last week.

The pandemic baffled physicians because-unlike seasonal flu, which is most dangerous for the very young and elderly-it proved most fatal for those between 20 and 40, she said.

It also moved rapidly through the body, in some cases within 24 hours from first symptoms to death, and most victims died of pneumonia, a secondary infection attacking the lungs after they were weakened by the virus. Antibiotics might have helped, but they had yet to be discovered.

Everyone was caught off guard in a patchwork, disorganized health care system, said Yanow.

New health system

Vincent Massey introduced a scathing critique of the Canadian response to the disease in Parliament in the fall of 1918, which led to the creation of the federal Department of Health, along with the first draft of Canada's pandemic plan.

That document included "five of the core pillars of a public health response we have today"-ensuring a uniform and coordinated response, issuing warnings, circulating evidence-based information and monitoring the disease while compiling statistics and tracking the pandemic's pattern of movement across the country, said Yanow.

What is less widely known is that the 1918 pandemic would continue to shape our understanding of influenza throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, she said.

Understanding influenza better

To start with, viruses had not yet been discovered at the time of the outbreak, but by 1931 the influenza virus was identified and could be cultured in a lab. By the 1950s, an animal model was developed to study the disease in a biological setting, said Yanow.

"There was keen interest to recover samples of the virus from people who died in 1918 and try to wake it up and put it in animals," she said.

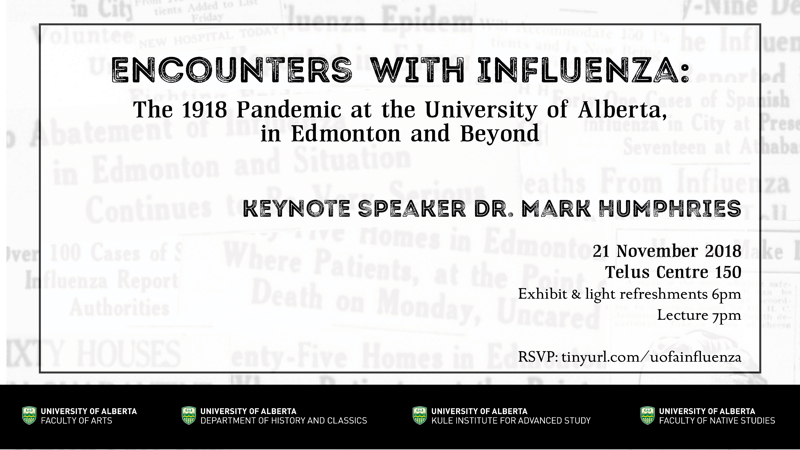

The Faculty of Arts is holding a panel discussion on the pandemic called "Encounters with Influenza: the 1918 Pandemic at UAlberta and Beyond" with keynote speaker Dr. Mark Humphries on Wednesday, November 21 at the Telus Centre. For more information and to RSVP, click here.